South Africa’s Legal and Court Systems

The South African legal system is a blend of British common law, Dutch-Roman law and “customary” law, reflective of its colonial history. Most courts follow South African common law, but will apply customary law when it is appropriate to do so. The common law, developed over the centuries, is largely rooted in the Dutch-Roman law brought by the Dutch in the 17th Century. British common law heavily influenced the development of the common law while South Africa was under the rule of the British Empire. These two legal systems gradually merged together to form South African common law, though it is still primarily considered a Dutch-Roman system.

As South African common law developed in colonial courts, the British created special courts that followed indigenous traditions, or “customary law.” The apartheid regime used this separate court system as a tool of racial segregation and privileged common law over customary law. When the apartheid regime ended, the new, human rights based Constitution legitimized customary law, making it an “equal partner to common law.” Common law and customary law alike are subject to Constitutional review.

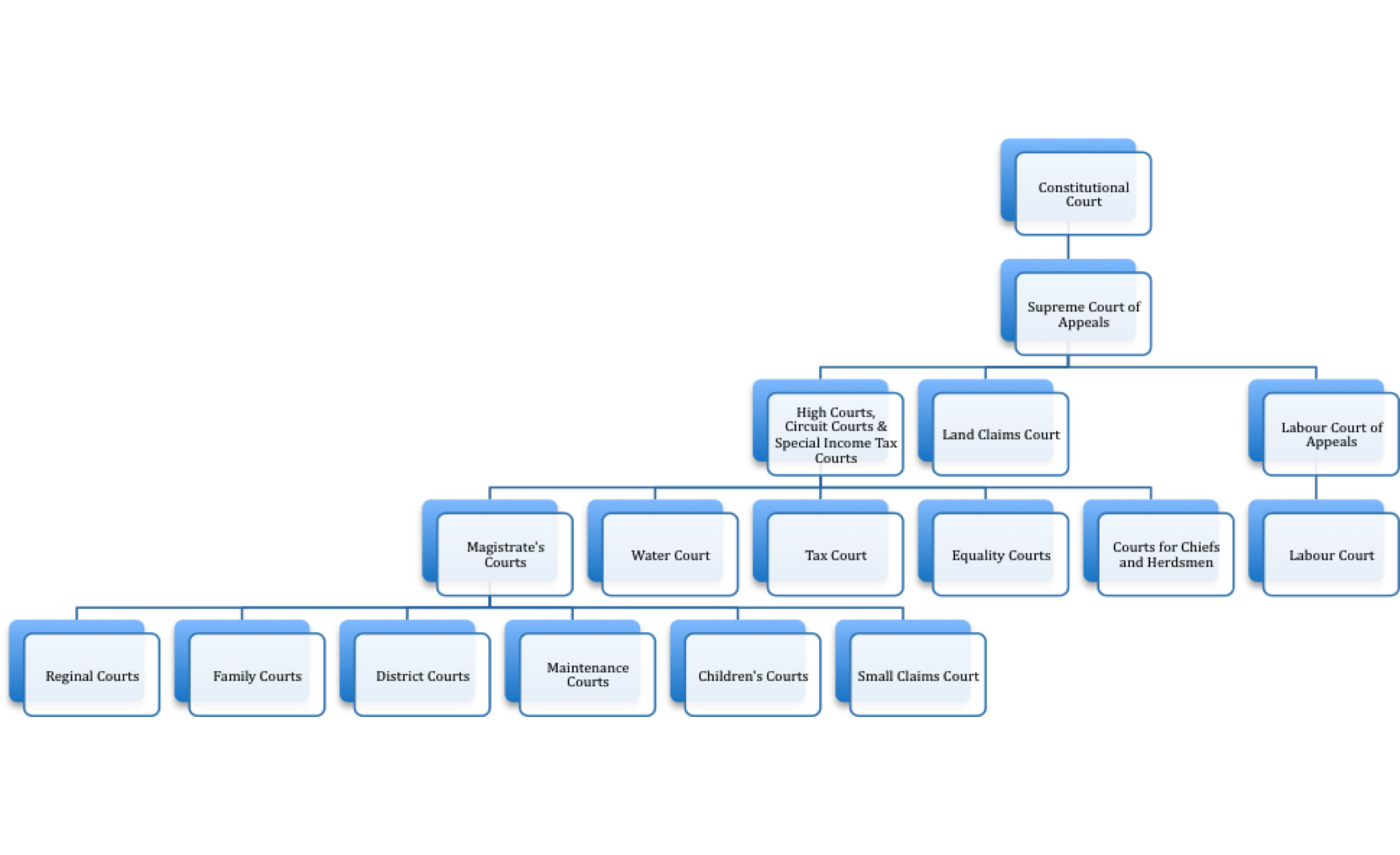

The South African Constitution establishes an independent judiciary, “subject only to the Constitution and the law.” The Constitutional Court of South Africa is the highest court of the nation on constitutional matters and has the power to decide issues of constitutional law. As a result, this Court may only review the decisions of lower courts if the decision was based upon constitutional law. In addition to reviewing the decisions of lower courts, the Constitutional Court may also decide the constitutionality of any amendment to the Constitution and any act of parliament or the president. Finally, the Constitutional Court is the sole court tasked with resolving issues or disputes about the powers and constitutional status of the branches of government. The Constitutional Court is located on Constitution Hill in Johannesburg.

The Constitutional Court is comprised of a Chief Justice, a Deputy Chief Justice and nine other judges. A total of eight judges must be present for the Court to hear a case. Generally, the Constitutional Court reviews the decision of lower courts, particularly the Supreme Court of Appeal. However, individuals may bring a matter directly to the Constitutional Court or appeal directly to the Court “when it is in the interests of justice” to do so.

Below the Constitutional Court is the Supreme Court of Appeals, located in Bloemfontein. The Court of Appeals is the highest court for all non-Constitutional matters, though it may hear Constitutional cases and arguments, subject to review by the Constitutional Court. As the name suggests, the Court of Appeals hears appeals from lower courts and its principle function is to review decisions from below. Generally, parties do not have an automatic right to appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeals; instead, leave to appeal must be granted in both civil and criminal matters. Unlike appellate Courts in the United States, the Supreme Court of Appeals may review questions of fact and questions of law since there are no jury trials. In addition to hearing appeals by the parties, the Minister for Justice and Constitutional Development may refer cases to the Supreme Court of Appeals if the decisions of the High Courts (discussed below) conflict with one another or if the Minister doubts the correctness of a legal decision in a criminal case.

The High Courts have the power to hear cases brought directly to them and appeals from lower courts. There are fourteen provincial divisions throughout the country and each division may only hear cases from within its geographical boundaries. Circuit Courts, another division of the High Courts, sit twice a year and move around rural areas to increase access to the courts. The Special Income Tax Courts also sit within the High Court and resolve tax disputes of more than R100,000.

Below the High Courts, there are Magistrates Courts, Small Claims Courts, and various specialty courts. The Magistrate Courts handle less serious civil and criminal cases while the Small Claims Courts may hear any civil dispute involving less than R7,000. The specialty courts include Equality Courts, Child Justice Courts, Maintenance Courts, Sexual Offence Courts, Children’s Courts and Labour Courts, all of which hear cases within their field of specialization. Decisions of these specialty courts are appealable to the High Courts, with the exception of the Labour Court. The Labour Appeal Court is the highest court for labour appeals.

THE FALL AND RISE OF TWO CHIEF JUSTICES

Gilbert Marcus *

Jason Brickhill +

THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY AND THE INSULATION OF THE JUDICIARY

The political revolution which occurred in South Africa on 27 April 1994 [1] was accompanied by a legal revolution which brought about a radical change in the country’s legal system. The system of parliamentary sovereignty, in terms of which Parliament could pass any law it pleased no matter how unreasonable or cruel [2] was replaced with a system of constitutional supremacy. Henceforth, all law and conduct would have to be constitutionally compliant. The Constitutional Court has described this process in the following way:

“The constitutional dispensation before and after 27 April 1994 differed drastically. The Interim Constitution was the instrument through which transition from an undemocratic order under parliamentary sovereignty to a democratic one under constitutional supremacy took place. The transition could be described as revolutionary, but insofar as this description is appropriate, the South African revolution was a negotiated and consequently a constitutionally and legally regulated one.” [3]

The superior courts were vested with the power of striking down enactments of the democratically elected Parliament. A new court, the Constitutional Court, was created as the final arbiter of all constitutional issues. All existing courts, both superior and inferior, continued to exist and all judicial officers retained their positions.

Those who drafted the Constitution were practical men and women. They recognised the need for legal continuity but also appreciated that the legal system had been tainted by apartheid. They addressed this dilemma by creating a Constitutional Court which was free of apartheid baggage and which would hopefully be constituted by judges with sufficient credibility to restore faith in the rule of law. They achieved their purpose admirably. The Constitutional Court has enjoyed enormous domestic and international prestige. But the problem of the old order judiciary was something which could only be addressed over time, largely by ensuring that racial and gender imbalances be addressed in the process of new appointments.

Inevitably, increasing focus would be placed on the judiciary. The political transition had seen the complete replacement of the legislature and the executive, but all judicial officers appointed under apartheid continued to wield power. Even the Constitutional Court included judges appointed under the old order but they were widely recognised as progressive judges who, in varying degrees, had done their best to curb the worst excesses of the apartheid legal order. [4] The political focus on the judiciary which has ensued in the past 18 years has taken many forms. There have been strident attacks on individual judges, on the courts as an institution and on particular judgments. These attacks have not been confined to disgruntled litigants. Sometimes they have emanated from powerful political figures and in the main, have been explicitly sanctioned by silence from the powers that be. The judiciary is, after all, a soft target. Many of the attacks have had a decided political flavour. Accusations of racism or, its euphemism, lack of transformation, have abounded. And, most concerning of all, senior political leaders have questioned the very idea of constitutional review.

The process of judicial appointments has also increasingly become an important battleground. One of the central constitutional reforms was to change the method of judicial appointments. Under apartheid, the system was intrinsically secret and undemocratic. All that was required was a nod from the Minister of Justice. The result was unsurprising. The vast majority of the all-white and almost exclusively male judiciary were comfortably in tune with the prevailing political morality, even if they were not card-carrying members of the National Party. This was all to change with the creation of the Judicial Service Commission (“JSC”) [5] . Politicians comprise the majority on the JSC. Of the twenty-three members, fifteen represent political interests, including the Minister of Justice. It has been pointed out that the ANC’s dominance in the political landscape means that “political representatives on the JSC who are either ANC members of Parliament or who are appointed by members who hold office by virtue of their membership of the ANC, currently have a majority of JSC seats, albeit by a small margin”. [6]

Since its inception, the JSC has conducted interviews of candidates applying for judicial office. These have taken place in public and are generally regarded as a significant improvement on the practice of the previous regime of secret and unaccountable appointments. The interviews themselves, however, have frequently been dogged by controversy, none more so than the recent hearings which resulted in the appointment of Chief Justice Mogoeng. That hearing in itself was precipitated by another extremely controversial episode: the attempt by President Zuma to extend the office of Chief Justice Ngcobo. Within the space of a few months, an intense spotlight was focused on the highest judicial office. It resulted in the demise of one Chief Justice and the rise of another.

THE FALL OF CHIEF JUSTICE NGCOBO

Constitutional Court judges are appointed for a fixed term. The matter is regulated, inter alia , by section 176(1) of the Constitution, which provides:

“A Constitutional Court judge holds office for a non-renewable term of twelve years, or until he or she attains the age of 70, whichever occurs first, except when an Act of Parliament extends the term of office of a Constitutional Court judge.”

The matter is further regulated by the Judges’ Remuneration and Conditions of Employment Act [7] (“the Judges’ Remuneration Act”) which, in broad terms, provides that a Constitutional Court judge is normally discharged from active service when he or she reaches the age of seventy or completes a twelve year term of office, whichever comes first. If, however, at that stage the judge has not completed fifteen years of active service, whether as a judge of the High Court or Constitutional Court, he or she continues in active service until completion of fifteen years or the age of seventy-five, whichever comes first. The Judges’ Remuneration Act, nevertheless, deals separately with the office of Chief Justice. Section 8(a) provides:

“A Chief Justice who becomes eligible for discharge from active service in terms of Section 3(1)(a) or 4(1) or (2), may, at the request of the President, from the date on which he or she becomes so eligible for discharge from active service, continue to perform active service as Chief Justice of South Africa, for a period determined by the President, which shall not extend beyond the date on which such Chief Justice attains the age of 75 years.”

Justice Ngcobo was appointed as a judge of the Constitutional Court on 15 August 1999. He had previously served as a judge of the High Court. His term of office, therefore, was due to expire on 14 August 2011. He was appointed as Chief Justice on 12 October 2009. During the early part of 2011, rumours began to circulate in the media that President Zuma was considering extending Chief Justice Ngcobo’s term of office. The Centre for Applied Legal Studies (“CALS”) wrote to the President and the Minister of Justice on 17 May 2011 enquiring whether the President was indeed contemplating extending Chief Justice Ngcobo’s term of office and expressing the view that section 8 of the Judges’ Remuneration Act was unconstitutional. [8] The letter made it clear that should the President exercise his powers under section 8 of the Judges’ Remuneration Act, there would be a challenge to its constitutionality.

The constitutional challenge foreshadowed in CALS’ letter seemed compelling.

Section 176(1) of the Constitution clearly contemplated the extension of judicial office. But it was explicit in prescribing the mechanism by which this could be done. What was required was “an Act of Parliament”. The proposition that delegation of this power was impermissible was strengthened by the very next sub-section, section 176(2), which deals with the position of judges other than Constitutional Court judges. It provides that such judges remain in office until discharged from active service “in terms of an Act of Parliament”. This formulation contemplates delegation of the power. By contrast, the formulation in section 176(1) seemed to rule out the possibility of delegation to the executive. Moreover, it was by no means clear that the Act of the Parliament envisaged in section 176(1) could be applied to a particular individual. Rather, its terms seemed to permit a generic extension of the terms of office of all Constitutional Court judges (and arguably all Chief Justices) but not a particular Justice or Chief Justice.

It transpired that the speculation about the extension of Chief Justice Ngcobo’s tenure was well founded. In fact, on 11 April 2011, President Zuma requested Chief Justice Ngcobo to continue to perform active service in terms of section 8(a) of the Judges’ Remuneration Act. In his letter, [9] President Zuma drew specific attention to section 8(a) of the Act and also stated that he took “cognisance of the critical role you have, of providing leadership to the Judicial Branch of Government”. Chief Justice Ngcobo was requested “to continue to perform active service as Chief Justice of South Africa from the 15 th August until 15 August 2016”. Chief Justice Ngcobo responded to this letter on 2 June 2011. His response justifies quotation in full: [10]

“Dear Mr President,

REQUEST FOR THE CHIEF JUSTICE TO CONTINUE TO PEROFRM ACTIVE SERVICE AS CHIEF JUSTICE OF SOUTH AFRICA

I refer to the letter from the President of 11 April 2011 requesting me to continue to perform active service as Chief Justice of South Africa.

I have carefully considered the reasons for the request and the period suggested by the President. I have decided to accede to the request and continue to lead the Judicial branch of Government during this critical time of the transformation of the Judiciary and Judicial system in South Africa.

A number of Judicial transformative initiatives have recently been undertaken by the Minister of Justice in Constitutional Development in collaboration with the Chief Justice and the Judiciary. Some of the most important programs which require leadership over the next five years are the following:

(i) the process of implementing Proclamation No. 44 of 2010 by the President establishing the Office of the Chief Justice as a national department located within the Public Service would only be completed over the next year;

(ii) the development of a model and policy in respect of the creation of an independent Office of the Chief Office in line with the independence of the Judiciary is only expected to be finalised over the next two years;

(iii) the establishment of the Constitutional Court as the apex court in South Africa and the constitutional recognition of the Chief Justice as the Head of the Judiciary and head of the Constitutional Court proposed in the Constitution Seventeenth Amendment Bill and the Superior Courts Bill, must still be piloted through Parliament and the subsequent implementation would have to occur over the next five years;

(iv) the Access to Justice Conference scheduled for July 2011, is expected to yield programmes to improve access to justice throughout the country, including the deep rural areas of South Africa, and their implementation would require the Judiciary to work together with the Minister of Justice and constitutional development over the next five years;

(v) consultation and negotiation with the Minister of Justice and constitutional development on the draft Judicial Code of Conduct and the Regulations for the Register of Registerable Interests of Judges, are currently underway;

(vi) the changes to the legislative framework for dealing with complaints on judicial conduct are only in the first stages of implementation and it is expected that substantial development to improve judicial accountability will take place over the next five years.

I am therefore in agreement with the President that a five year term is appropriate and adequate to place the independence of the Judiciary, judicial accountability and access to justice on a sound footing and continuity in leadership is vital at this stage of these transformative changes.

Warmest Regards.

I am, sincerely,

S SANDILE NGCOBO

CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA”

The following day, the President extended the term of office of the Chief Justice and communicated this decision to the JSC and to leaders of the political parties represented in the National Assembly, before he announced his decision in an address to Parliament. [11]

The Chief Justice’s response to the President’s invitation is remarkable for a number of reasons. At the level of principle, it is surprising that the Chief Justice would have so readily acquiesced in the extension of his own appointment in circumstances where he, of all people, must have been acutely conscious of the risk that such extension would be unconstitutional. He would, in all probability, have been aware of the letter from CALS to the President and the Minister of Justice. Even if this letter had not come to his attention, the matter had already attracted debate in the media.

More importantly, however, whether or not Chief Justice Ngcobo was alive to the concerns raised by CALS, he could not have been oblivious to his own judgment in Executive Council, Western Cape v Minister of Provincial Affairs and Constitutional Development [12] which dealt with a similarly worded section of the Constitution. The case concerned section 159(1) of the Constitution which required the term of a Municipal Council to be determined “by national legislation”. Section 239 of the Constitution defined “national legislation” to include subordinate legislation made in terms of an Act of Parliament. In the judgment of Justice Ngcobo, as he then was, (concurred in by all the other Justices) it was held that Parliament could not delegate its power in terms of Section 159(1) to the Minister. He stated:

“The Constitution uses a range of expressions when it confers legislative power upon the National Legislature in chap 7. Sometimes it states that ‘national legislation must’ and other times it states that something will be dealt with ‘as determined by national legislation’ and at other times it uses the formulation ‘national legislation may’. Where one of the first two formulations is used, it seems to me to be a strong indication that the legislative power may not be delegated by the Legislature, although this will of course also depend upon context.” [13]

Justice Ngcobo, however, articulated a point of principle. He stated:

“Given its importance in the democratic political process, and given the language of section 159(1), the conclusion that section 159(1) does not permit this matter to be delegated by Parliament, but requires the term of office to be determined by Parliament itself, is unavoidable. In addition to the importance of this matter, I also take cognisance of the fact that it is one which Parliament could easily have determined itself for it is not a matter which requires the different circumstances of each municipal council to be taken into consideration. All that is required is to fix a term which will apply to all councils. In my view, this is not a matter which the Constitution permits to be delegated. The delegation was, therefore, impermissible …” [14]

Given this judgment, it is inconceivable that Chief Justice Ngcobo was not alive to the risk of the extension of his appointment being declared unconstitutional. That he took the risk was therefore regrettable in itself. But perhaps more controversial was the content of his letter of acceptance. He did not simply accept the President’s invitation. Instead, he chose to explain why it was such a good idea for his tenure to be extended. It was scarcely surprising that this move was described as “lobbying to stay on”. [15]

The threatened challenge became a reality. [16] Given the urgency of the matter, the Constitutional Court convened during recess. [17] Two days before judgment was due to be handed down, Chief Justice Ngcobo made a dramatic announcement. He stated that he had withdrawn his acceptance of the President’s invitation. In a statement issued by the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, the reasons for the withdrawal were given. Chief Justice Ngcobo had apparently taken the decision “in order to protect the integrity of the Office of the Chief Justice and the esteem of the Judiciary as a whole”. He apparently “found it undesirable for a Chief Justice to be a party in litigation involving the question of whether or not he or she should continue to hold office as this detracts from the integrity of the Office of the Chief Justice and the esteem with which it is held”. [18]

The news of the withdrawal was met with mixed reactions. Some commentators saw the decision as an act of selflessness. Professor De Vos wrote that “by resigning, Chief Justice Ngcobo is displaying the kind of integrity and respect for his office and for that of the Constitutional Court that those of us who have always admired him, came to expect from him”. He went on to argue that “it spares us all from the rather destructive effects of a long drawn out fight”. [19]

Eusebius McKaiser, by contrast, thought it “surprising” that Chief Justice Ngcobo was “receiving mostly uncritical praise for his decision”. His standpoint was that the Chief Justice had been “aware for months already that there is compelling doubt about the constitutionality of the statutory clause in terms of which the President had made him the offer to stay on”. He went on to state:

“He should have either gently alerted the Presidency to these concerns back then or declined the offer. The timing of this withdrawal is curious. One cannot but help speculate that the embarrassing prospect of one’s constitutional peers handing down a judgment that inadvertently shows you to have acted self-interestedly, rather than with sound constitutional sense, motivated this last minute withdrawal.” [20]

Regrettably, McKaiser’s view regarding the timing of the withdrawal may be more in accordance with the facts. It has been suggested above that Chief Justice Ngcobo must have been well aware that the extension of his office was constitutionally vulnerable before the litigation commenced. A concern for the integrity of his office and the judiciary as a whole would have compelled him to decline acceptance of the President’s invitation at the outset. But that was not the only opportunity that he could have seized. He was a named respondent in the litigation. The papers were served upon him. Once proceedings were initiated, that too would have been an opportunity to avoid being a (passive) party to the litigation. [21] Instead, however, he waited for the matter to be argued in court and only on the eve of judgment chose to withdraw.

Why Chief Justice Ngcobo thought that his withdrawal would bring an end to the litigation, presumably by avoiding the need for any judgment, is also not clear. In the midst of the litigation, there was a serious endeavour by the Ministry of Justice to introduce new legislation to remedy the perceived problem with the Judges’ Remuneration Act. This development featured prominently in the debate before the Constitutional Court even though the precise legislative contours of the proposed remedial legislation were unknown. Indeed, counsel for both the President and the Minister of Justice urged the Court to consider whether section 176(1) of the Constitution permits Parliament to single out the Chief Justice for purposes of extending an incumbent’s term of office. [22] The reason for this request flowed from the possibility of remedial legislation that would have singled out Chief Justice Ngcobo and permitted his tenure of office to be extended.

Unsurprisingly, the Constitutional Court unanimously declared section 8(a) of the Judges’ Remuneration Act to be unconstitutional. It followed that the decision of the President to request Chief Justice Ngcobo to continue performing active service as Chief Justice was inconsistent with the Constitution and invalid. [23] Three (unnamed) members of the Court, while agreeing that section 8(a) was invalid on the basis of the differentiation it effected, did not agree that section 176(1) never permits differentiation on the basis of the office that the Chief Justice holds. In other words, these three were of the view that Parliament could extend the term of office of the Chief Justice, but this could only be effected through an Act of Parliament “of general application which rationally pursues a legitimate governmental purpose” and, in particular, that such a measure “must further judicial independence”. [24] Thus the door to remedial legislation singling out Chief Justice Ngcobo was effectively closed.

The failure of President Zuma’s attempts to extend Chief Justice Ngcobo’s tenure of office necessarily meant that the office became vacant. A Bill introduced in the midst of the furore around the extension, which would have provided for a minimum term of seven years after appointment as Chief Justice or President of the SCA, has now been withdrawn. [25] The Constitutional Court judgment and the announcement that Chief Justice Ngcobo was withdrawing his acceptance of the extension were to presage yet another controversial event: the appointment of Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng.

THE RISE OF CHIEF JUSTICE MOGOENG

The Constitutional Court judgment was followed by public speculation as to the possible successors to Chief Justice Ngcobo. Media reports, citing unnamed sources, suggested that the likely candidates included Deputy Chief Justice Moseneke, Justice Sisi Khampepe, President of the Supreme Court of Appeal, Lex Mpati, and others.

As it happened, President Zuma announced that he intended to nominate Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng for appointment as Chief Justice. On 18 August 2011, Justice Mogoeng wrote to the JSC to accept the nomination of President Zuma as a candidate for Chief Justice. In his acceptance, as is required for all JSC interviews, he disclosed his personal and professional particulars, and his most significant contributions to the law and the pursuit of justice. He highlighted certain judgments that he had delivered and his roles within the judiciary in processes relating to judicial education, case-flow management and access to justice. This was the beginning of a short, but dramatic, period of public comment and the interview proceedings before the JSC.

THE PUBLIC COMMENTS ON JUSTICE MOGOENG’S NOMINATION

On 20 August 2011, the JSC passed a resolution stating that it would issue an invitation to legal professional associations and other institutions with an interest in its work to make written submissions to it “on the suitability of the nominee by the President for appointment as the Chief Justice”. [26] Twenty-one sets of comments were lodged with the JSC by interested parties, predominantly civil society organisations and professional associations.

Significant among the public responses were the comments of COSATU and leading legal and other non-governmental organisations, opposing Justice Mogoeng’s appointment as Chief Justice. The position taken by COSATU was significant given that the trade union federation forms part of the tri-partite alliance, together with the African National Congress and South African Communist Party, which governs South Africa. The comments opposing the appointment generally addressed four themes: gender insensitivity; Justice Mogoeng’s antagonistic approach to homosexuality; concerns relating to judicial ethics; and his lack of experience in constitutional matters.

We do not recount all 21 sets of submissions, but highlight two significant submissions by COSATU and Section 27, a leading legal NGO.

COSATU disagreed that Justice Mogoeng lacked the necessary (minimum) experience for appointment as Chief Justice, but expressed concerns relating to certain of his decisions on gender-related and sexual violence, equality and sexual orientation and his role as a State Prosecutor in the apartheid era. COSATU referred to five of Justice Mogoeng’s decisions as a High Court judge relating to gender-related and sexual violence: S v Moipolai , [27] S v Mathibe , [28] S v Modise , [29] S v Mathule [30] and S v Serekwane . [31]

COSATU also referred to the decision in Le Roux v Dey , a case in which the plaintiff had alleged, among other things, that he had been defamed by being portrayed as homosexual . [32] In a section concurred in by all the Justices except Mogoeng J, [33] the judgment held that ‘[a]n actionable injury cannot be based solely on a ground of differentiation that the Constitution has ruled does not provide a basis for offence.’ [34] Mogoeng J did not provide reasons in the judgment for declining to support this proposition. Noting that it was difficult to draw conclusions from this judgment alone, especially since Mogoeng J had not explained his position, COSATU proposed that Mogoeng J should be required to explain the matter before the JSC. [35]

Finally, COSATU addressed Justice Mogoeng’s role as a State Prosecutor before democracy. COSATU noted that, in the past, a background as a prosecutor had disqualified other candidates because of the “history of prosecution of politically motivated cases on what was an illegitimate state”. COSATU noted, in particular, that Justice Mogoeng had acted for the Bophutatswana Government in 1991 in opposing an application to stay an execution in a death penalty case.

COSATU concluded its submission as follows:

“On the basis of our concerns we cannot support the appointment of Justice Mogoeng for the position of Chief Justice, which we believe he would hold for the next 10 years if successful. Moreover, while this is not presently for the consideration of the JSC, it is disturbing that even if NOT successful Justice Mogoeng will remain on the bench as an ordinary Constitutional Court judge.

Whereas the reality is that questions as to his fitness and appropriateness to serve as a judge in ANY court, let alone the Constitutional Court, raises serious concerns as to the nature and rigour of the original process that enabled him to ascend to the bench.

This highlights the need to ensure a process that will seek [to] democratise the way judicial appointments are made.

Mogoeng proves the correctness of the theory that says “black is not equal to transformation”. Ultimately we need a new beginning with a transformed judiciary that is sensitive, accessible and accountable, and which has as its focus the interests of the marginalised, the acceleration of development, justice and socio-economic justice in particular. Mogoeng does not reflect any class bias and we do not believe that he is capable of taking forward the objective of transforming the judiciary.

Based on his remarks, it is evident that he reflects an insensitive, patriarchal and backward mindset that is chauvinistically inclined towards the stereotypical role of women. His appointment would be a slap in the face of millions of black, and African women in particular, who have championed the rights and interests of women, and would constitute a reversal of the struggle for total women emancipation.

Accordingly we are calling on the JSC to recommend against Justice Mogoeng’s appointment and to further call on the State President to review and re-open the nomination process in order to identify more suitable candidates.” [36]

Section 27, a legal NGO, made a submission in its own name and on behalf of other prominent organisations, namely Sonke Gender Justice Network, the Lesbian and Gay Equality Project and the Treatment Action Campaign. The organisations expressed the “firm view” that Justice Mogoeng was not suitable for the position of Chief Justice, [37] addressing similar themes to COSATU.

First, section 27 addressed the issue of Justice Mogoeng’s approach to sexual orientation, referring to the Constitutional Court judgment in Le Roux v Dey discussed above. Section 27 noted that judges are constitutionally required to give reasons for their decisions. [38] Section 27 complained that the issue was not whether Justice Mogoeng was right or wrong to dissent, but rather that the public were entitled to know the extent of his dissent, why he dissented and whether he is in fact able to discharge his oath of office. [39] Section 27 argued that this is particularly so given Justice Mogoeng’s membership of Winners Chapel South Africa, the local branch of David Oyedopo Ministries International that preaches that homosexuality is a perversion that can be cured. [40] Section 27 recommended that the JSC question Justice Mogoeng on his dissent. [41] Section 27 also proposed that the JSC require Justice Mogoeng to make a public commitment to protect the rights of LGBTI persons. [42]

Section 27 then turned to consider Justice Mogoeng’s approach to gender based violence. Section 27 referred to some of the judgments discussed in the COSATU submission, expressing concern at what it considered to be a “trend of patriarchy in a line of judgments of Justice Mogoeng relating to cases of gender based violence”. [43] Having reviewed these judgments, Section 27 stated that they reflected that Justice Mogoeng “reached for arguments akin to ‘she asked for it’, ‘she wasn’t really hurt’, ‘he was understandably sexually aroused’ and ‘it wasn’t really that bad because he was not a stranger’”. [44] In the view of Section 27, these arguments were not befitting a judicial officer let alone one who occupies a seat on the Constitutional Court. [45] Section 27 concluded that it, and the organisations joining its submissions, had “no confidence in [Justice Mogoeng’s] ability either to dispense justice in accordance with the values of the Constitution or in his ability to address the complex gender questions that arise in the judicial and in the legal profession appropriately”. [46] Section 27 considered that the judgments to which it had referred evidenced “a patriarchal attitude to woman”, adding that they had no reason to believe that Justice Mogoeng would not exhibit similar patriarchy in relation to gender transformation in the judiciary, the legal profession and indeed society as a whole. [47]

Section 27 concluded its submission by stating its “firm view” that “ Justice Mogoeng is not suitable for the position of Chief Justice of South Africa” [48] . In addition, section 27 called on the JSC to conduct an open and accountable interview and consultation process, including conducting a public interview of Justice Mogoeng open to all media (including broadcast media), as well as to committing to publishing the advice given to the President on the suitability of his nominee for appointment as Chief Justice of South Africa. [49] As we discuss below, the JSC responded favourably to some, but not all, of Section 27’s suggestions regarding the process.

Justice Mogoeng published a detailed, 38-page, written response to the various comments submitted to the JSC by interested parties. [50]

Justice Mogoeng started by addressing the theme of gender sensitivity, discussing each of the judgments that had been raised by interested parties in their comments. Justice Mogoeng asserted that sound reasons were given for all the sentences imposed in these matters. [51] To the extent that he was criticised for leniency, he referred to other cases in which he had dealt with the perpetrators of rape firmly. [52] He added that the reasoning employed in the criticised judgments was similar to the reasoning adopted by other appellate judges in different cases. He stated:

“The sentences imposed may differ but the reasoning we all employed is essentially the same. If the submissions based on gender sensitivity were to be upheld, then at least all the above judges will also be unfit for judicial office.” [53]

Justice Mogoeng then turned to address the complaints relating to his attitude towards sexual orientation. Justice Mogoeng began by asserting that his church’s opposition to homosexuality was similar to the position of other Christian churches and was not one of the core values of the church. [54] He affirmed that he had made a public commitment to uphold the constitutionally entrenched rights of the gay and lesbian community [55] .

Regarding the complaint about his failure to give reasons for his position in Le Roux v Dey , Justice Mogoeng noted that the paragraphs that he declined to endorse related not only to gay people but also to other categories of persons, including Christians. [56] He added that he had not had sufficient time to provide proper reasons for his position and accordingly decided not to provide reasons so as not to hold up the judgment. [57]

Justice Mogoeng then turned to address criticism of his professional ethics. A complaint had been made that he had failed to recuse himself when his wife appeared before him in an appeal. In this regard, he indicated that he had consulted with other senior judges who had assured him that there was nothing wrong with his wife appearing before him and that he had taken the position that she would only appear before him in appeals. [58] He also noted that close family members of other judges had appeared before those judges in various matters and provided annexures listing the matters in which specific practitioners appeared before their fathers. [59] Justice Mogoeng argued that this situation was analogous to that of his wife appearing before him. [60]

Justice Mogoeng next addressed concerns about his age and seniority. Regarding his age – 50 at the time of nomination – he provided four examples of Chief Justices of comparable age when appointed elsewhere in the world, including John Roberts, who was appointed Chief Justice of the United States at the age of 50. [61] Regarding experience, he referred to his service as Judge President of the North West for 7 years, arguing that he had “a track record for taking measures to enhance access to justice, court efficiency and the independence of the judiciary.” [62] He further referred to his work in the National Case Flow Management Committee and the Access to Justice Conference as demonstrating his capacity to lead the judiciary. [63]

In response to the complaints that he had worked as an apartheid prosecutor, Justice Mogoeng explained that he came from a poor background and when offered a bursary by the Boputhatswana Government in 1981, he accepted it. He explained that, because his political standpoint was known to his superior, he was not allocated political trials as a prosecutor. [64] He explained that he prosecuted persons accused of murder, robbery and rapes and that he had no regret for having done so and was also not apologetic about the bursary. [65] In relation to the matter of State v Ngobenza , an application for a stay of execution, he explained that it was an urgent application assigned to him by his superior. [66] He added that at the time, the death penalty had not yet been abolished and that the New Constitution did not exist. [67] He also related that in 1992 or 1993, he had appeared in a radio debate about the death penalty, arguing for its abolition. [68]

Justice Mogoeng then turned to deal with some of the specific judgments raised by other commentators. In particular he discussed judgments in which the SCA had set aside his decision on appeal. He explained that, in relation to State v De Beer , “the SCA set aside my decision and I took it as a lesson” [69] . In relation to the case of Molotlegi & Another v Mokwalase , Justice Mogoeng said “here I got the law completely wrong. It does happen to all of us sometimes. Besides our Court system has appeal procedures precisely because it is recognised that judicial officers are human beings and may therefore err in their decisions. It would then be for an appeal court to correct whatever error they have made.” [70]

In conclusion, Justice Mogoeng reaffirmed his commitment to upholding and protecting the Constitution and the human rights entrenched in it. He argued that he is neither homophobic nor gender insensitive when it comes to the rape of women and concluded as follows:

“I decide cases based on the facts and the Constitution and the law. And if I am appointed as the Chief Justice, I will continue to do so, as I have done for the past 14 years as a judicial officer.” [71]

Against the background of these written submissions and the written response of Justice Mogoeng, the JSC convened a public hearing.

THE ‘INQUISITION’: THE JSC INTERVIEW PROCESS

AIDS activist organisation the Treatment Action Campaign gathered to protest at the JSC interview venue, making a statement that the TAC was “firmly of the view that he [was] not a suitable candidate”, explaining that a study of his judgments showed “patriarchy” and leniency towards rape and women abuse. [72] Professor Calland described the scene of the interviews to be held in the “sleek modernity of Cape Town international Conference Centre”, the venue for “the hottest ticket in town”. [73] He commented that “[r]anged against Mogoeng [was] a formidable band of representatives of the legal profession and the human rights community, who raise formidable and serious issues of objection to the presidential nominee.”

The interview proceedings were broadcast live on a national radio station and on a pay-per-view national television channel, with portions broadcast on national free-to-air television. The interview proceedings ran over an unprecedented two days and dominated local media for several days. Many members of the legal profession attended the proceedings, including judges and practitioners who travelled to Cape Town for the purpose.

Following discussion about whether the JSC should consider other possible candidates, the JSC resolved not to do so but to begin Justice Mogoeng’s interview. Justice Mogoeng began by reading to the JSC, verbatim, his written response to the submissions made by interested parties. The members of the JSC, chaired by Deputy Chief Justice Moseneke, took turns to ask questions. Niren Tolsi provides the following account of the drama and its principal actors:

“If the JSC interview were a boxing match, then minister Jeff Radebe would undoubtedly be Mogoeng’s sweat-dabber in the corner, towel at the ready to dry the brow – or staunch the blood – between rounds.

Radebe and the three ANC MPs on the JSC, including deputy ministers Fatima Chohan (home affairs) and Ngoako Ramatlhodi (correctional services) together with Advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza (one of four presidential appointees to the JSC) were instrumental in ensuring Mogoeng had breathing space between probing, questioning combinations with much softer questions and observations.” [74]

Some of the more striking moments of the hearing included Justice Mogoeng telling the chair, Deputy Chief Justice Moseneke, not to be “sarcastic” when pressed to explain his “jurisprudential position” for dissenting in Le Roux v Dey . [75] Justice Mogoeng later admitted that he had “erred” in not providing reasons for his position. [76] It was reported that, during the JSC interview, “[Justice] Mogoeng shared many tense exchanges with Deputy Chief Justice Moseneke, although he later apologised saying ‘There is not a single human being who never loses his or her temper’.” [77]

Another striking moment was the exchange with MP, Koos van der Merwe, relating to Justice Mogoeng’s statement that he had prayed and got a signal that he should accept the nomination. The exchange between van der Merwe and Justice Mogoeng was reported as follows:

“Do you think God wants you to be appointed chief justice?

– I think so.

That creates a problem for me. If I vote against you, what is God going to do to me?

– That is between you and God, commissioner.” [78]

At the end of the JSC proceedings, Chief Justice Mogoeng gave a media statement that, if appointed, he would “ensure that no judicial officer would suffer the way [he] did” in the days between his nomination and his two-day interview, referring to the “intensity of pressure and comments made about [him]” in the media. [79] He also assured women, as well as the gay and lesbian community, that their rights would be protected and that he hoped to unite the judiciary by making it “a priority to reach out” to members of the Constitutional Court and other courts, including those critical of his nomination. [80]

Following the interview proceedings, the JSC met behind closed doors to deliberate and vote. The majority of the JSC voted to support President Zuma’s nomination of Justice Mogoeng. [81]

Several commentators criticised the decision of the JSC on the basis that it had failed to discharge its constitutional duty. As to the substance of the decision, the JSC was criticised for merely asking whether Justice Mogoeng fulfilled the formal requirements for appointment and not whether he was an “exceptional” candidate or considering his nomination in light of other possible nominees. [82] Section 174 of the Constitution provides that the President may appoint the Chief Justice after consulting the JSC and heads of the opposition parties represented in the National Assembly. The leader of the Democratic Alliance also complained that the President had not adequately consulted her, after the President cancelled a meeting scheduled to discuss the issue. [83]

In our view, a purposive interpretation of section 174 of the Constitution does require the JSC, when consulted by the President, to advise the President on the merits of potential appointees beyond simply confirming that a nominee meets the formal requirements for appointment. [84] The function of minimum threshold vetting could be met without involving the JSC at all. During the interview, Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development, Jeff Radebe, surprisingly referred to the “minimum” requirements for appointment of a Chief Justice in terms of the Constitution, stating that Justice Mogoeng met these requirements and implying that this was the end of the JSC’s enquiry. [85] It would be startling, however, if the President were to assert that he did not wish to appoint an excellent (if not the ‘best’) candidate but would be satisfied with appointing someone with the formal qualifications for appointment as Chief Justice. [86]

More debatable is whether it is appropriate for the JSC to propose other possible candidates to the President. However, comparison among candidates may be necessarily implied in any substantive assessment of the President’s nominee for appointment.

THE BENEFITS AND LESSONS OF THE JSC PROCESS

In a media briefing to announce his decision to appoint Justice Mogoeng to the position of Chief Justice, President Zuma said that the manner in which Chief Justice Mogoeng had responded to what he called the “spirited public commentary on his candidature” had protected the integrity of the Constitutional Court and the judiciary. [87] President Zuma commented:

“Chief Justice, you maintain[ed] a dignified silence and only responded to the criticism at the correct forum, the JSC. The judiciary should not be part of mud-slinging and other spats that happen from time to time in society.” [88]

Speaking at the same press conference, Chief Justice Mogoeng described the process surrounding his nomination and interview as “a tsunami of a special kind”. [89]

While Chief Justice Mogoeng undoubtedly experienced the JSC process and ‘spirited’ public commentary as unpleasant, in our view the transparency and openness of the JSC interview process and the increased public participation are to be strongly welcomed. It is indeed deeply unfortunate that the concerns about his suitability that were voiced in the process, most of which pre-dated his 2009 JSC interview and appointment to the Constitutional Court as an ordinary justice, were not raised earlier.

Following the appointment of Chief Justice Mogoeng, there has been heightened interest and participation in the judicial appointment process generally, in particular among the legal professional bodies. The General Council of the Bar and the constituent Bars have taken steps to ensure that all applicants for judicial appointment are now reviewed and comments are furnished to the JSC. Civil society organisations have also increased their participation in the process.

There is also heightened scrutiny over the JSC itself, but commentators continue to express concerns at its institutional ‘capture’ and loss of independence. Tolsi’s prediction of the voting of the JSC on Justice Mogoeng reflects a deeply troubling general understanding of the independence of members of the JSC:

“The JSC, whose 23 members will vote by secret ballot on whether to endorse the president’s nomination of Mogoeng, are likely to find in his favour with the body having enough Zuma appointees (four) and ANC members (three MPs, four National Council of Provinces members and Radebe) to have a 12-11 majority.” [90]

In the JSC as constituted in the past, there was never any suggestion that the members appointed by the President, who included George Bizos SC and Kgomotso Moroka SC, were bound, or even expected, to endorse candidates preferred by the President. Worryingly, commentators now suggest that the four presidential appointees are partisan and that the members of the JSC no longer exercise independent judgment, but operate as a caucus on instructions of the ruling party, as we discuss below.

However, we reiterate that the greater openness and transparency of the JSC proceedings is to be strongly welcomed, and may in future serve to enable the public (including civil society and the legal profession) to influence the approach of the JSC to questions such as the threshold for ‘suitability’ and the degree of independence required of JSC members in future.

CONCLUSION: PRESIDING UNDER SCRUTINY

Chief Justice Mogoeng stands to serve a term of a decade at the head of the judiciary, a significantly longer term than his two immediate predecessors, Justices Langa and Ngcobo. This period will, in all likelihood, be a significant one in shaping South Africa’s nascent constitutional jurisprudence and influencing the institutional culture of the Constitutional Court. [91] Unlike his predecessors, Chief Justice Mogoeng faces the challenge of considerable media and professional scrutiny over his conduct as Chief Justice and the substance of his decision-making, as a result of the events described above.

Already, there has been one fresh incident resulting in commentators raising questions about the Chief Justice. Reports emerged that the Chief Justice had sent an email requesting senior judges to attend a leadership conference to be conducted by a well-known American evangelical speaker. [92] The request sparked controversy in the media, with anonymous judges and members of the legal profession reportedly complaining (anonymously) that the Chief Justice had acted inappropriately in appearing to instruct colleagues to attend a conference with specific Christian content hosted at a church. The Mail & Guardian quoted several senior judges, speaking on condition of anonymity, as reacting with “astonishment” and “deep concern” to the request and complaining that it showed “religious insensitivity” and “blurring of church and state”. [93] The heads of court responded to the media storm by issuing a statement in support of Chief Justice Mogoeng, in which they said that “[t]he invitation was not to a religious event but to a leadership conference, which nobody was ordered or compelled to attend.” [94]

Prominent journalist, Mondli Makhanya, reacted strongly to this incident, using the issue to rehash the JSC proceedings leading to Chief Justice Mogoeng’s appointment. [95] Makhanya asserted that the Chief Justice’s request relating to the conference has proved right those who questioned his suitability for appointment. He accused the JSC of “moral cowardice” in supporting the appointment, which he described as “the worst decision in the JSC’s 15 years of existence”. Makhanya provides the following analysis of what he calls the “capture” of the JSC:

“While the institution started off as a collection of the strongest minds from the legal, political and academic worlds, today it is hard to vouch for its collective wisdom and integrity.

Not that they are intellectually lacking. Rather it is that many of them lack moral steel. Instead of doing what is right and selecting the best candidates, they follow a Luthuli House [96] brief. The philosophy of many on the commission seems to be: ‘Ask not what is good for the country, but what the party mandarins want.’

Makhanya gloomily predicts that this philosophy is likely to prevail with future appointments and that “the Constitutional Court has already been identified as the next target for capture. And the already captured JSC will be the instrument with which this capture is carried out.” Makhanya warns that South Africans should brace themselves for “more Justice Mogoengs”, adding that he considers that it will be “hard for anyone to match the wackiness of our current chief justice”. [97]

All of this makes for a fraught and tension-filled atmosphere within which Chief Justice Mogoeng must perform his function as Chief Justice. At the time of the appointment, although some civil society organisations indicated that they were considering a legal challenge to the appointment, [98] the consensus that appeared to emerge in civil society was that such a challenge would be unlikely to succeed and would, whatever the result, do damage to the administration of justice.

Arguably, rehashing the JSC proceedings and the debate around the appointment today also threatens to destabilise the judiciary. However, the media has already shown that the appointment debate remains fresh in the memory and that the concerns about his suitability are likely to be repeated whenever the Chief Justice attracts any fresh controversy. This leaves the Chief Justice operating under close and constant public scrutiny, not only in his judgments, but whenever he acts as head of the judiciary, especially where matters of religion, sexuality and gender arise.

As Chief Justice, he will also now chair the proceedings of the JSC. It is to be hoped that the gains in terms of transparency and openness will not be sacrificed on the back of Chief Justice Mogoeng’s criticism of the process following his nomination. Crucial questions relating to the proper role of the JSC and its members and the constitutional standards by which to judge candidates for appointment to the judiciary are likely to continue to arise during the tenure of Chief Justice Mogoeng.

HBO COMPETITION FINALIST – August 2010: Martha’s Vineyard African American Film Festival

Courting Justice has been shown at

The United Nations, Embassies and Consulates, U.S. Department of State, South Africa Parliament, Library of Congress, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and the Law and Society Association.

Film festivals and media around the world, including festivals in Burkina Faso, China, Ethiopia, France, India, Iran, Philippines, South Africa, the United States and Zimbabwe.

- Voice of America.TV

- SABC (South Africa Broadcasting Corporation)

- Durban International Film Festival, Audience Award

- PSBT Open Frame (India)

- Sichuan TV Festival (China)

- Addis International Film Festival

- Encounters Film Festival (Johannesburg and Cape Town, South Africa)

A number of festival screenings have been at prominent women’s film festivals, such as

- The UNIFEM Women’s International Film Festival

- International de Films de Femmes de Creteil(Paris)

- International Images Film Festival for Women

- Women Without Borders Film Festival

Courts, judicial organizations, bar associations and law firms

— (selections in alpha order)

- American Society for International Law

- Association of the Bar of the City of New York (which premiered Courting Justice in the United States)

- Black Lawyers Association

- International Association of Women Judges

- Nassau County Supreme Court

- National Association of Women Judges

- New York State Bar Association

- New York Women’s Bar Association

- Sedgwick, Detert, Moran & Arnold

- South Africa Constitutional Court

- U.S. Court of International Trade

Law schools — (selections in alpha order)

- Cornell School of Law

- Fordham Law School

- Georgetown University School of Law

- Harvard Law School’s Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice (where the audience included former U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and Archbishop Desmond Tutu)

- New York University School of Law

- University of Maryland Law School

- University of Pittsburgh Law School

- Valparaiso University Law School

- Washington College of Law Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Law, American University

- Yale Law School

Colleges and Universities — in Australia, Canada, South Africa and the United States. At most of the academic institutions where Courting Justice has been shown, the library has purchased the film, making it available for multiple classes and for student private viewings.

Middle Schools and High Schools in South Africa and the United States, where the brief history available on this web site has been of special use to teachers. Click here for a page featuring comments made by some of the young students in South Africa after watching Courting Justice.

Churches among which was the Union Baptist Church in Durham North Carolina, where a panel of three African American women judges responded to the film, connecting their life stories to those told by the featured South African women judges.

Organizations and Community Centers — (selections in alpha order)

- American Association of University Women/D.C. Branch

- Harvard Club in New York City

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Centennial Meeting

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Mid-Manhattan Branch

- New York Women’s Forum

- Sherman, Connecticut Jewish Community Center

- Southern Coalition for Social Justice

- U.S. Committee for UNIFEM

- Vance Center for International Justice Initiatives

- Women’s Justice Center

- Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

- YMCA and YWCA in Urbana-Champaign, Illinois